Building effective supervision relationships

Part of Reflective Supervision Hub > Practice Supervisor resources

Select the quick links below to explore the key sections of this area for Building effective supervision relationships.

Relationships Using agreements Supervision history What you bring Power, difference and discrimination

Seeking feedback Courageous conversations Interprofessional supervision Final reflections

Introduction

As a practice supervisor you need to:

-

Be able to build effective supervision relationships in diverse teams.

-

Create supervision agreements setting out how you can work together effectively.

-

Be prepared to have courageous conversations.

-

Have regular conversations with your supervisees about how the supervision relationship is being experienced.

-

Understand how your own supervision history can help you think more about the power and impact of supervision- including what is helpful and what is not.

-

Be able to talk about power, privilege and discrimination with supervisees. Fear of being misunderstood or causing offence means that this can feel awkward or uncomfortable, but it is important to break the silence and talk about these issues.

This section explores building effective supervision relationships and what that means for practice. The content has been adapted from publications developed as part of the Practice Supervisor Development Programme (PSDP) funded by the Department for Education.

-

Addressing barriers to the progression of black, Asian and ethnic minority social workers to senior leadership roles by Bernard (2020)

-

Critical conversations in social work supervision by Chandra (2020)

-

Having courageous conversation as a practice supervisor by Chesterman (2020)

-

Using the supervision relationship to promote reflection by Guthrie (2020)

-

Using supervision agreements by In-Trac Training and Consultancy (2019)

-

Your supervision history by In-Trac Training and Consultancy (2019)

-

Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and the LUUUTT model by Partridge (2019)

-

Lifeline exercise by Sturt (2019).

Before you start working through this section, please spend a moment or two thinking about:

- A time when supervision was going well.

- Either as a supervisee or supervisor.

- Any moment no matter how small.

What comes to mind when you think about:

- What was happening at that moment in supervision?

- Why does that moment stand out?

Keep this in mind as you read the information that follows. We will revisit this activity at the end.

As In-Trac (2019a) explains, it is important to build safe and trusting relationships with the people you supervise so that they can get the most out of supervision.

When practitioners feel safe, they can reflect more deeply about:

- how they communicate and build relationships with people who draw on care and support

- how exposure to trauma, hardship and loss through their work may impact them

- how they use power in their roles

- ethical dilemmas and practice challenges.

Supervision relationships that support reflection are based on five key principles:

- Connection – a safe emotional connection, based on respect, trust and a sense of safety

- Collaboration – both parties feel that their voice is heard, and that they can explore experiences, ideas, values and feelings

- Containment – the supervisee understands that the supervisor will cope if strong emotions are expressed (and feels safe to do so)

- Maintenance – attention is paid to how the relationship develops over time. Any ruptures or difficulties are acknowledged and discussed

- Agreements – both parties are clear about their expectations of each other and how they should work together (Hewson and Carroll, 2016).

-

Can you think about a supervision relationship where you felt safe to reflect? Does it match up with the principles above?

-

Which of the five principles do you feel confident with as a supervisor? Which is more of a struggle?

-

Can you think of a time when you have repaired a rupture within a supervision relationship? How did you do this? What was the impact of this repair on the supervision relationship?

Adapted from Guthrie (2020).

Using supervision agreements

Supervision agreements outline the expectations supervisors and supervisees can have of one another. They also provide an opportunity to agree how you will work through any challenges you may face in working together (for example disagreements or giving each other feedback).

Using the language of an agreement, rather than a contract, highlights the role that both of you play in developing an effective supervision relationship. Supervision agreements are often negotiated at the start of a supervisory relationship. But, if that is not possible, they can be set up at any time. They are usually reviewed once a year.

A supervision agreement discussion allows you to jointly explore:

-

the purpose of supervision

-

how you will work together

-

expectations of each other

-

priorities (making clear what is negotiable and what is not)

-

how you will talk about difference and diversity

-

how you will give each other feedback and manage disagreements.

(In-Trac, 2019a)

The discussion also gives you an opportunity to find out more about what makes your supervisee tick. For example, you might want to ask about their:

-

previous experiences of supervision (including what was helpful and what was not)

-

stage of professional development, achievements and ambition

-

preferred learning style.

Adapted from Earle et al. (2017)

It is also useful to ask your supervisee about any hopes, fears or anxieties they may have about working together. This sends an important message that anything can be discussed in supervision.

-

What do you hope supervision will provide?

-

What are you anxious about?

-

Which issues do you feel more confident in discussing?

-

What issues might you need encouragement to discuss?

-

Which subjects might you prefer to avoid?

-

How comfortable are you in talking about your feelings?

-

How will I know if I am getting it wrong?

-

How comfortable do you feel to be challenged?

Morrell (2008, p.28)

One of the main tasks of the practice supervisor is to provide support and guidance. Sometimes, though, you may need to give constructive or developmental feedback to a supervisee about their performance. It is useful to highlight that this is part of your role during a supervision agreement discussion so that your supervisee is clear about this.

![]() Supervision agreement template - You can use this example to jointly negotiate a supervision agreement with a supervisee. (you can type directly into it)

Supervision agreement template - You can use this example to jointly negotiate a supervision agreement with a supervisee. (you can type directly into it)

- What do you think is most important to include in a supervision agreement discussion?

- How can you support supervisees to contribute to supervision agreements?

- What would you like to do differently having read the information in this section?

Understanding your own supervision history can help you:

-

think about the power and impact of supervision

-

reflect on your own experiences and identify how supervision can be helpful and when it is not

-

recognise when you need to adapt your style to meet your supervisee needs.

![]() Your supervision history tool: practice supervisor - You can use this tool to think about your own experience of supervision and reflect on your learning from this.

Your supervision history tool: practice supervisor - You can use this tool to think about your own experience of supervision and reflect on your learning from this.

Asking your supervisees to also reflect on their experiences of supervision is a helpful way of starting to understand what they need from you and to explore how they learn best in supervision.

This also allows you to learn more about any adverse experiences that might influence how your supervisee uses the supervision space or interacts with you.

Adapted from In-Trac (2019b). You might want to ask your supervisee:

- When has a supervisor been helpful to you in the past?

- What did they do that was helpful?

- What did you like about the kind of supervisory relationship they established with you?

- Why was that important to you?

Understanding what you bring to supervision

As a practice supervisor it is important to be aware of influences and experiences which have shaped you.

For example:

-

personal and professional life experiences

-

histories and stories about yourself and others

-

the cultures and communities you grew up in or identify with.

Thinking about these things can help you consider how you can build supervision relationships in diverse teams where you may be working across race, ethnicity, class, age, sexuality etc. You have a responsibility to help your supervisees think about these issues too so that they can practice in a socially-just, ethical way that meets the needs of diverse communities.

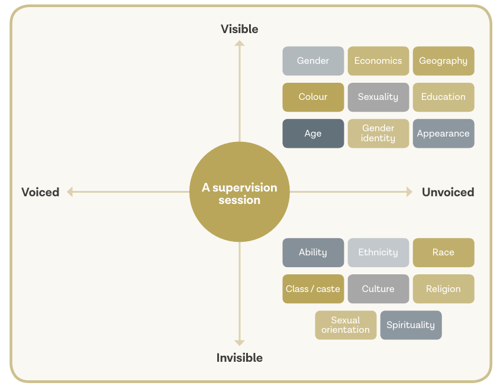

The social GGRRAAACCEEESSS

The social GGRRAAACCEEESSS, developed by Burnham (2013), is a helpful tool to start thinking about how aspects of personal and social identity give us less or more power in different contexts in society. Adapted from Sturt (2019).

The tool captures parts of our personal and/or social identity that can be voiced or unvoiced and visible or invisible.

If you have read other chapters in this learning hub you may have come across the tool already, which is flexible and helps us explore the impact of power, discrimination and disadvantage. It can be used in several ways to support supervision practice.

(A large view of the tool can be viewed in the downloadable tool below, What shapes you as a practice supervisor?).

Here we are talking about how using the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS with your supervisee can:

-

help make important aspects your identities more visible

-

create a better understanding of one another

-

support connection and collaboration.

(A large view of the diagram can be viewed in the downloadable tool below, What shapes you as a practice supervisor?).

We often think about the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS in terms of bias or difference. However, they can also help us understand where we can have strong affinity with, or connections to, others

(Sturt, 2019).

![]() What shapes you as a practice supervisor? - To think further about the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and reflect on the influences that have contributed to your identity.

What shapes you as a practice supervisor? - To think further about the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and reflect on the influences that have contributed to your identity.

Talking about power, privilege and discrimination in supervision

Structural inequalities are endemic in society and can easily be mirrored in supervision relationships.

-

Supervisees may not feel comfortable talking about their own experiences of discrimination and how it affects their work.

-

Fear of being misunderstood or causing offence means that supervisors may find it awkward or uncomfortable to talk about power, privilege and discrimination with people they supervise.

It is important to break the silence and discomfort that can arise when speaking about the impact of structural inequalities on people’s lives. This allows you to create an environment in which potentially sensitive issues of unequal power, discrimination and disadvantage can be brought into the open and discussed. Adapted from Chandra (2020).

Example: thinking about the impact of racism.

Have a look at the examples below which illustrate the impact of workplace racism within social work organisations.

Have a look at the examples detailed below which illustrate the impact of workplace racism within social work organisations.

- ‘Black and Global Majority social work professionals report frequently experiencing racism from their point of entry on to social work programmes and through their careers as social care professionals.’ (Tedam, 2022)

- Workplace racism is a barrier to career progression for Black and Global Majority workers who are often overlooked for development opportunities.

- There is a lack of racial diversity in senior management roles in social services departments. White men overwhelmingly make up most management roles in social work.

- The numbers of Black women at senior management levels are low. Black women seldom achieve managerial positions because of intersecting systemic racism and sexism.

- Deficit-informed presumptions by managers is a major barrier for Black women. Undervaluing their skills and attributes results in managers having low expectations and overlooking their potential for promotion to managerial roles.

Adapted from Bernard (2020)

The issues as explored above often remain underground and unexplored even though their impact is frequently felt by Black and Global Majority practitioners, particularly those who are also marginalised in other ways.

This means that Black and Global Majority practitioners often feel disempowered in speaking about their experiences of racism (O’Neill and del Mar Fariña, 2018).

-

As an individual practice supervisor, you can’t change the system single-handedly. However, you can play an important role in breaking the silence about racism in supervision.

-

You can also play a key role in supporting Black and Global Majority practitioners to develop and progress by focusing on these areas in supervision.

Adapted from Chandra (2020)

-

How able do you feel to introduce conversations about power, difference and discrimination into supervision relationships?

-

Are there any areas of structural discrimination where you feel more or less comfortable? How do they relate to your social GGRRAAACCEEESSS?

-

What are your experiences of how power and authority have been constructed in previous supervision relationships? How do these experiences impact upon you as a practice supervisor?

-

Who can support you to develop your thinking and practice in this area?

Guthrie (2020)

Seeking feedback about supervision

Like all relationships, supervision relationships benefit from regular conversations about how both parties are experiencing them.

-

Scheduling regular reviews (e.g. every six months) can be a useful way to do this.

-

These don’t necessarily need to be formal or take a long time. You could, for example, agree to end your usual supervision discussions a little early and spend a few minutes reviewing how you work together.

The purpose of a review is to share your perspectives about how you work together in supervision and how this might be improved.

Being relationally reflexive means moving away from thinking about what is discussed in supervision to being curious instead about how you and your supervisee interact with each other in supervision. In other words, the kind of working relationship you have.

The concept of ‘relational reflexivity’ can be helpful when thinking about reviewing supervision.

(Burnham, 2005)

Taking the initiative to talk about something that you have noticed about a supervision relationship during a review involves taking a ‘relational risk’ (Mason, 2005). If you are not used to doing this, it can feel a bit awkward at first. It can also feel risky for your supervisee given the authority and power you have as a practice supervisor.

-

It can be helpful to ‘warm the context’ by offering an introduction explaining that you are inviting reflections about your working relationship (Burnham, 2005).

-

It is also helpful to have highlighted in your supervision agreement discussion that you will regularly check in with your supervisee seeking their views about their experience of supervision with you as well as giving your own feedback.

Giving and receiving feedback in this way strengthens the relationship between you and your supervisee and supports reflective discussions in supervision.

-

How do you feel about asking for feedback from a supervisee about how they are experiencing your relationship, and what they are finding helpful or unhelpful about supervision?

-

How do you think they might respond?

-

What might you do or say to encourage them to share their views and experiences openly with you?

Adapted from Guthrie (2020)

Having courageous conversations

Practice supervisors sometimes need to have courageous conversations with the people they supervise.

One of the functions of supervision is to hold practitioners to account for their work. It is important to be open with supervisees that this is part of your role and that you may need to give feedback about:

-

a supervisee’s performance or competence

-

an ethical issue or concern

-

something that is not working in your supervision relationship.

A courageous conversation starts with the practice supervisor naming what the issue is and their view about what needs to change, before seeking the supervisee’s perspective. Many practice supervisors say they find it difficult to have these conversations. For example, if the issues are complex or challenging, or when they think a supervisee will find it difficult to hear or disagree with the feedback. Because of this, it can be tempting to put these conversations off or not have as detailed or as honest a conversation as you would like.

Feeling that you are ‘having to walk on eggshells’ with a supervisee is a useful prompt for you to consider if a courageous conversation would help. As Davys, 2019, p.83, 'when we feel uncomfortable, it can be hard to listen to each other’s perspectives. If the discussion is not handled well the relationship between you can deteriorate'.

Therefore, good preparation for courageous conversations is essential.

Adapted from Chesterman (2020). Before you meet with your supervisee it is helpful to think about:

-

what you want to achieve

-

what feedback you want to give and receive (and why)

-

how you might structure a courageous conversation

-

how you can support a supervisee to develop their work further.

These questions are useful prompts to think about when preparing for a courageous conversation:

-

What is the issue which needs addressing?

-

Is there more than one issue?

-

Why is the issue important?

-

Why is it challenging for me to address this issue with this person?

-

What are my feelings about this issue?

-

What are my feelings about the person concerned?

-

What are my feelings about me and my role in this situation?

-

How might those feelings affect the conversation?

-

Can I articulate the issue?

-

Do I have examples of behaviour or events which illustrate the issue?

-

What is the message I wish to communicate?

-

What is the outcome I am seeking from this conversation?

-

What is my motivation for having this conversation?

Beddoe and Davys (2016, p. 197)

Interprofessional supervision

Interprofessional supervision means supervising the work of someone from a different profession. It is not unusual to be asked to do this. For example, it is quite common in multi-disciplinary teams in adults’ services.

When you start to supervise someone from a different profession, it’s even more important to discuss what each of you need, to make sure that this works well. This is because people from different professional backgrounds may approach supervision differently. Differences in language can also sometimes be a challenge, leading to misunderstandings (Davys, 2017).

To avoid this, make sure that you are clear about:

-

your supervisee’s role, responsibilities and how they operate within their team

-

professional values or approaches that inform your supervisee’s work

-

professional language that is commonly used.

It is also important to jointly think about:

-

who your supervisee is accountable to for their work.

-

if this is not you, how will you monitor what is happening and how will your supervisee update you?

-

whether your supervisee will need additional support from someone in the same profession and how this might work.

![]() Supervising someone from a different professional background - Read more in this tool about interprofessional supervision.

Supervising someone from a different professional background - Read more in this tool about interprofessional supervision.

Practitioners value being able to ask for support and advice from someone from their profession who has worked in the same area of practice (Tanner et al, 2023).

Providing your supervisee with a mentor from the same profession can be very helpful here. As well as being a point of contact for any ad-hoc queries this person can help your supervisee to discuss:

- clinical practice issues

- professional identity

- transferring skills, knowledge and values into a professional CPD framework.

-

Don’t be frightened – you don’t have to know everything about the other profession.

-

Encourage your supervisee to see the positives of interprofessional supervision.

-

Be clear about the limits of supervision and where else support will come from.

-

If you can’t give the person what they need then help them find someone else.

There are many benefits to supervising someone from a different professional background. Practice supervisors who have done this often say that they find this valuable and that it gives them new perspectives and knowledge (Davys, 2017).

-

What areas of accountability or expectations about practice might you need to clarify in interprofessional supervision?

-

What support would you need from your line manager when supervising someone from a different profession?

Consider a time when supervision was going well:

- Either as a supervisee or supervisor.

- Any moment no matter how small.

What comes to mind when you think about:

-

What was happening at that moment in supervision?

-

Why does that moment stand out?

When we ask people to do this activity, they usually identify moments in supervision in which they felt:

-

connected

-

heard

-

understood

-

relieved

-

supported

-

able to share feelings

-

helpfully challenged

-

guided about how to proceed

-

that new learning or insights had emerged.

We usually remember these things, no matter how small, even if they occurred some time ago. It may well be that you have thought of something similar.

Moments like these are only possible when there is a strong and effective working relationship between practice supervisor and supervisee.

In fact, the quality of the relationship you build with supervisees has a direct bearing on how much they can reflect in supervision

(Guthrie, 2020).

Therefore, paying attention to building effective supervision relationships with the people you supervise is crucial.

Beddoe, L., and Davys, A. (2016). Challenges in Professional Supervision: Current Themes and Models for Practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bernard, C. (2020). Addressing barriers to the progression of black, Asian and ethnic minority social workers to senior leadership roles. Research in Practice.

Burnham, J. (2005). Relational reflexivity: a tool for socially constructing therapeutic relationships. In Flaskas, C., Mason, B., and Perlesz, A. (Eds). The Space Between: Experience, context, and process in the therapeutic relationship. Karnac.

Burnham, J. (2013). Developments in Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS: visible-invisible, voiced-unvoice. In Krause, I. (Ed). Cultural Reflexivity. Karnac.

Chandra, C. (2020). Critical Conversations in Social Work Supervision. Research in Practice.

Chesterman, M. (2020). Having courageous conversation as a practice supervisor. Research in Practice.

Davys, A. (2017). Interprofessional supervision: A matter of difference. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 29 (3), 80-94.

Davys, A. (2019). Courageous conversations in supervision. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 31 (3), 78–86.

Earle, F., Fox, J., Webb, C., and Bowyer, S. (2017). Reflective supervision: Resource Pack. Research in Practice.

Guthrie, L. (2020). Using the supervision relationship to promote reflection. Research in Practice.

Hewson, D., and Carroll, M. (2016). The Reflective Supervision Toolkit. MoshPit Publishing.

In-Trac Training and Consultancy. (2019a). Using supervision agreements. Research in Practice.

In-Trac Training and Consultancy. (2019b). Your supervision history. Research in Practice.

Morrell, M. (2008). Supervision contracts revisited: Towards a negotiated agreement. Aotearaoa New Zealand Social Work Review, 1, 22-31.

Mason, B. (2005). Relational risk-taking and the therapeutic relationship. In C. Flaskas, B. Mason, and A. Perlesz. (Eds). The Space Between: Experience, context, and process in the therapeutic relationship. Karnac.

Nosowska, G. (2025). Supervising someone from a different professional background. Research in Practice.

O’Neill, P., and del Mar Fariña, M. (2018). Constructing critical conversations in social work supervision: Creating change. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46(4), 298-309.

Partridge, K. (2019). Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and the LUUUTT model. Research in Practice.

Sturt, P. (2019). Lifeline exercise. Research in Practice.

Tanner, D., Willis, P., Beedell, P., Nosowska, G. (2023). Social Work with Older People - The SWOP project: Main Findings, NIHR School of Social Care Research, University of Birmingham, University of Bristol and Effective Practice.

Tedam, P. (2022). Promoting anti-racism in children and family services. Research in Practice.

Reflective supervision

Resource and tool hub for to support practice supervisors and middle leaders who are responsible for the practice of others.