I don’t care if I get paid more, I just need there to be less work.

These were the comments made by a senior social worker following a reflective workshop I had undertaken a year ago. Within two months she had left the organisation.

My role is as an Advanced Practice Lead within my local authority, supporting the objectives of the Principal Social Worker and promoting best practice within the organisation. Early into my role I identified that one of the biggest barriers to improving practice is the pressure of caseloads that practitioners are under.

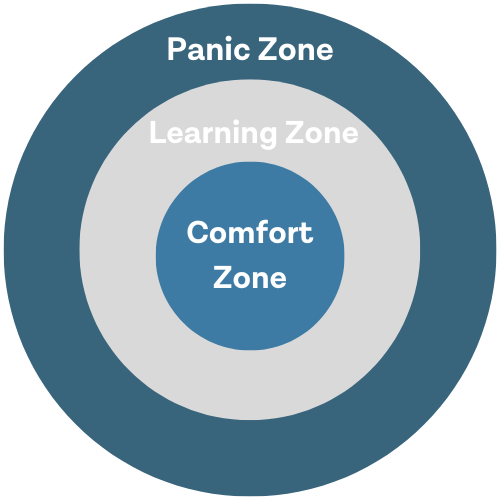

Social pedagogy encourages practitioners to see any daily life situation as a potential learning opportunity. The Learning Zone Model frames this as three zones, comfort, learning and panic.

The comfort zone includes things that are familiar and the learning zone includes what you need to do to advance – you need to leave the comfort zone to learn and grow.

However, beyond these two zones is the panic zone – when learning becomes impossible. Operating in the panic zone means you are overwhelmed and blocked by a sense of fear because you are trying to cope with the stress.

The Learning Zone model

Unfortunately, most practitioners are continuously operating within the panic zone. Having come from direct practice I also had first-hand experience of the negative impacts of stress and so the words of the practitioner weighed heavy on my heart.

Social work is facing significant issues with recruitment and retention nationally. This is detrimental to the profession, but also, more importantly, to the service we provide to the people we support.

These factors led me to question if there is a more effective way of being able to measure caseloads to prevent overload and burnout, ensure healthy working conditions for practitioners and seek to promote the best service for people. A manageable caseload has been identified in the literature as a key aspect of ensuring social workers remain in their roles. The desire for healthy practitioners was echoed in a podcast by Social Work England, where an expert by experience stated that:

The better frame of mind my social worker is, the better service they can provide me… I’ll get better services if they are well taken care of but also from their point of view they'll be able to do a better job and come out of it a lot more satisfied and more fulfilled from doing their job.

To address this, I was awarded an NHS Research & Development North West Social Care Practitioner Researcher Internship, which gave me time out of my role to consider the research regarding caseload weighting for adult social care social workers.

I undertook a literature review on identifying robust caseload weighting tools, however found that whilst there were articles on the development of such tools there was no evidence of their effectiveness.

This identified a gap and failed to give me an evidence base on which to make recommendations to the local authority on weighting tools that could be implemented.

I found this surprising given since 2009 there has been work by the Social Work Task Force, Social Work Reform Board and Standards for Employers of Social Workers In England.

Through research I have also found several published caseload measurement tools that all reiterated the importance of manageable and safe workloads for social workers and occupational therapists to protect both them and the people they support:

- Applying Clinical Reasoning: A Caseload Management System for Community Occupational Therapists.

- Building a safe and confident future: Proposals from the social work reform board.

- Compiling a Caseload Management System for Mental Health Case Management.

- Regional Workload Management Framework for Social Workers in Adult Services.

- Supervision and Workload Management for Social Work.

As a caveat I recognised that there were (and still are) other external factors that influenced the workload demand on social workers, such as the impact of New Public Management and austerity.

This would seem to support Moriarty and Manthorpe’s findings that organisational changes to structures within social work do not always come from research evidence.

However, in practice a social worker will still need to advocate for when their caseload had gone beyond their capacity to manage and an effective way to do so is needed.

Supervision should be the tool by which social workers negotiate with their managers to ensure that they are not overburdened, however this does not always occur in practice.

This isn’t an issue that is going to go away. One potential solution is to adopt a caseload allocation tool for use in supervision and contribute to the research evidence on the effectiveness of doing this on social worker wellbeing. Another is to adopt an indicative caseload limit as outlined in the ‘Setting the Bar’ report undertaken for social work in Scotland.

This is very much the beginning of a journey and since undertaking the Practitioner Researcher Internship I have focused on embedding a research culture within adult social care and housing, developed a research strategy and worked with internal and external partners to achieve this.

I hope to now turn to undertaking a research project to establish an effective way to support social workers to manage caseloads in the short-term, whilst considering potential wider systemic changes that could also address this.

I believe the people we support deserve the best service possible and ensuring their social workers wellbeing is a key aspect of this.