Understanding equity

Part of the 'Equity Change Project'

Introduction

In intersectionality, context is crucial. The understanding of inequity and the response to this repositions shame and blame from the individual to the situations they inhabit. This section explores the idea of equity. It will help you think about how to have conversations about equity and how to make inequities visible.

Lived experience of equity

Clenton Farquharson spoke of his experience of working for equity:

Equity demands that we acknowledge inequalities and actively work to level the playing field. It's not a passive race but an intervention. To achieve equity, we must first recognise the unfairness of the starting line. Then, we take action: redistribute the weights, remove obstacles, and provide support to those weighed down.

Equity isn't charity; it's justice in action. It's a relentless pursuit of a world where the weights no longer dictate your chances. Equity doesn't settle for ‘equal chances’ on an unequal battlefield. It's the commitment to dismantle the systems that create disparities and provide everyone with an unburdened path to success. In this race, equity isn't just an option; it's the only way to ensure that the finish line truly represents equal opportunity for all.

Understanding equity

Intersectionality demands that we think about each person’s specific identity and context. This is the route to equity. We can only achieve equity if we see each person as they are and act with them to overcome the compound impact of the vehicles of oppression intersecting at their particular crossroads.

In adult social care, equity means recognising the unique needs of each individual and providing support that is tailored to their specific circumstances. People need ‘the right fit’ not ‘one size fits all’. Just as different people require different shoe sizes and styles to ensure a comfortable fit, equity recognises that individuals have different needs and backgrounds, and face different challenges. Equity emphasises the importance of providing the necessary support, resources and opportunities to each person based on their unique circumstances. The aim is for everyone in the community to be valued and thriving.

Co-production can help us design an equitable system. For example, Social Care Future’s vision is:

(Social Care Future, n-d)

This is in contrast with what might be termed the ‘professional gift’ model, which offers what the service deems people should want and demands that everyone is happy with what they get.

The value of intersectionality is that it explicitly names and foregrounds social inequities, types of oppression and unequal power relations, providing a whole view of the interplay of the person’s identity and experiences. Therefore, intersectionality provides a way of co-producing a clear picture of where the person is and how they are injured. This allows a response that is personal, tailored and works to overcome the specific barriers that this person faces.

Reflective question

In your work, how do you use the words equity and equality?

Discarding the Master's tools

Audre Lorde (1979) wrote that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. To move from inequity to equity we need to use different tools and strategies from the tools that created the inequity. The Change Project began with a data scope that showed that adult social care is infused with, and reproduces, inequity. So, we need to rethink our approach, practice and response.

Some aspects of social care and social work practice have always sought to challenge the systems that oppress or hold people back. Activism alongside people with lived experience has already achieved positive change in a number of areas. The social model of disability, anti-oppressive practice and strengths-based practice are all such examples. See for example our Radical Safeguarding Toolkit, strengths-based practice and disability and housing resources to explore some of these ideas further. Intersectionality brings these and other ways of resisting systemic inequity into a single view.

When we see things as they are and can name them, we can then join up the approaches that lead to positive change. Individual actions add up. For example, writing a person-centred assessment rather than a bureaucratic record for the benefit of the agency can make a big difference for that individual (see here for resources on analysis and critical thinking in assessment). Each action starts to change the way people experience the system. But system-wide actions are also needed, and we explore these within the Leadership and System change sections of this change project.

Reflective question

In your experience, what are the master’s tools in adult social care?

How can we think beyond the systems and processes we are used to, to do things differently and bring about change?

Use this tool below to reflect on the idea of the master's tools.

This tool helps you to consider what causes inequity and the importance of thinking and acting differently to bring about change.

Power, privilege and position

Power can play out in a single look.

Change Project participant

Oppression is based on power. It is legitimised through the idea that one person is better than another.

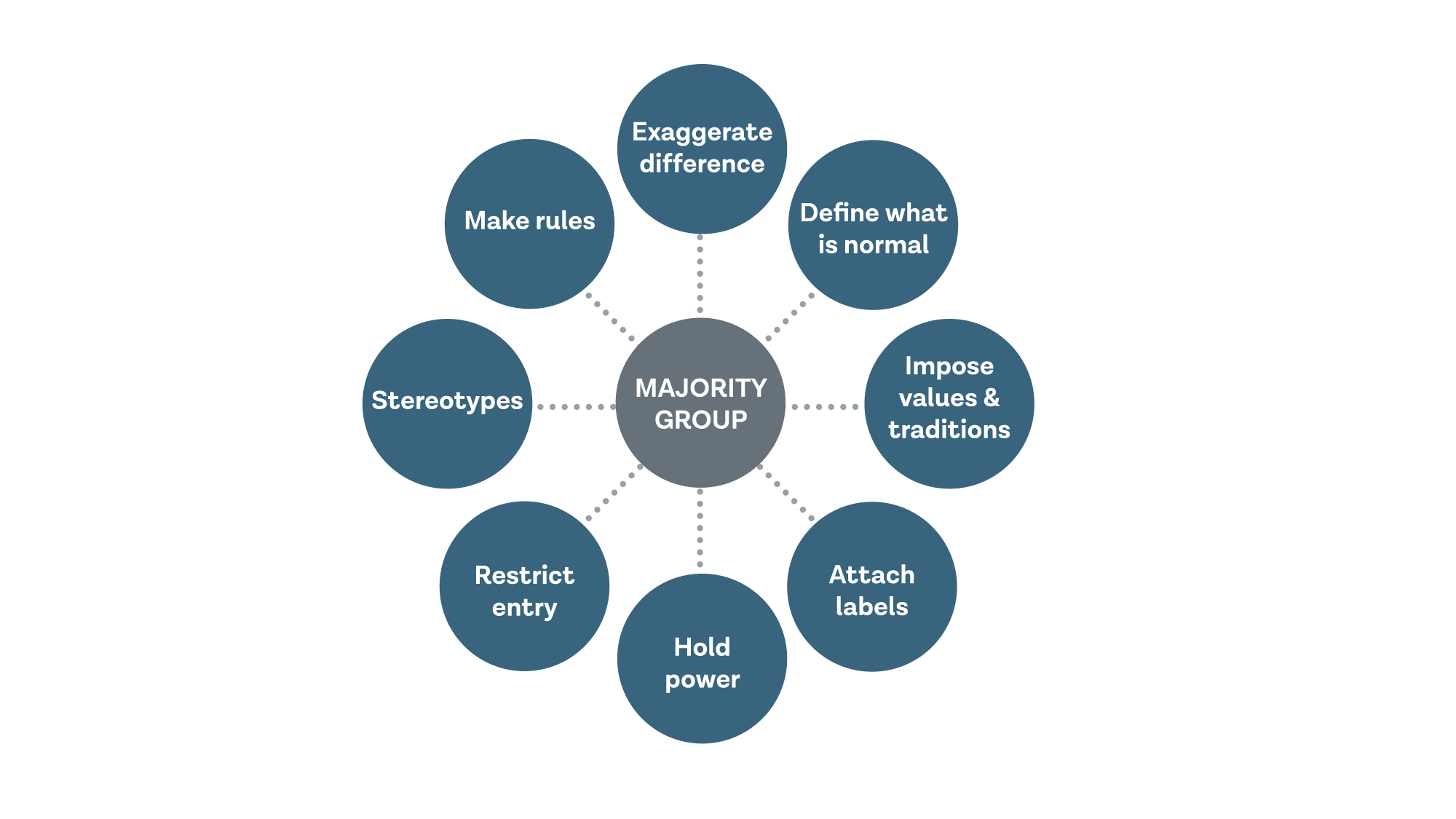

The diagram below depicts structures and strategies (both conscious and unconscious) that are used by majority groups to keep control and hold power (Clements & Spinks, 2009). While each strategy has a particular technique and impact, they are linked. All forms of control rely on multiple tactics. For example, when someone is denied a voice, they may not be allowed into a meeting in which they are stereotyped and labelled. The intersection of strategies of control makes it harder for people to exercise their power.

(Clements & Spinks, 2009)

In adult social care, power comes from expert knowledge, authority (the sanctioned use of power) or control. Power can be used to dominate, to undermine or to force change. It is important to think about where power is in the system and why it is there. It was designed into the system. You may be interested to read our chapter on ‘Sharing power as equals’ from our co-produced resources working towards a brighter social care future.

The way adult social care is structured means that services often create a division between the people they are for (for example, adults with a learning disability) and the people they are not for (for example, adults with autism). This categorises and divides people. People have multiple strands to their identity, and services designed to meet a specific need may not take account of this.

Intersectionality enables us to see and name the power dynamics. Intersectional empowerment involves understanding the person and their context, and removing the barriers that stop them from exercising their power.

Reflective question

Where do you see power coming from and being used in adult social care?

Use this tool below to reflect on how systems divide people and how more connection can be enabled.

This tool considers the fragmentation and connection in systems, particularly the systems we work in, and how we can make these visible so that changes can be made.

White supremacy

The dominance of white people in our society and the power of white people across the globe influence the current social care system; its policy and practice, as it does all institutions (DiAngelo, 2021). For example, white people are over-represented in leadership roles within adult social care (Adult Principal Social Workers Network, 2017), and social workers from a Black, African, Caribbean or Black British background are more likely than white social workers to have fitness-to-practice concerns progress to a hearing by the regulator (Social Work England, 2023). This does not mean that people who identify or are identified as white do not experience racism, and this must be countered. However, it is to recognise that the conditioning that we all experience – that white is the default for humans – results in daily experiences of inequity for those who do not fit that category. For example, this includes racially minoritised people facing questions about their hair, food, names or origin that white people usually do not.

DiAngelo writes that everyone is socialised into racism. And when we recognise that this has happened to us, it can be deeply challenging. What’s important is what we do with this knowledge. We can bring social care knowledge and experience of the impact of context, culture and society to reflect on how being socialised into an inequitable world affects us individually. We can draw on this awareness of ‘the social’ to question our own privilege and to build commitment to anti-racist practice. This resource is one way of enhancing our ability to do the work of anti-racism better, building on the commitment that already exists across the sector. For change to happen, white people need to push past feelings of guilt that might get in the way of action, and instead take accountability for the impact of that socialisation and use their privilege to interrupt the way that this aspect of power manifests.

Anti-racist action is required. This is more than being non-racist – it’s about actively challenging the explicit and implicit assumptions that privilege whiteness (Ahmed, 2021). Intersectionality comes from grassroots Black feminism. It therefore offers a countering force to assumptions of power. Intersectionality expects us to name white supremacy for what it is, so that we can dismantle its influence and increase equity.

Reflective question

How does white supremacy show up in your day-to-day work, including in work you do around equality, diversity and inclusion?